The quintillions of different runs in Hades (and why it doesn't matter)

Let's conjure the old god Combinatorics' most overpowered boons.

Combinatorics is an area of mathematics primarily concerned with counting, both as a means and an end in obtaining results, and certain properties of finite structures. It is closely related to many other areas of mathematics and has many applications ranging from logic to statistical physics, from evolutionary biology to computer science, ... and game design!

My favorite games are similar to great standup comedy shows. Every minute a new punchline is dropped and I'm thinking to myself "Oh shit, that's fun". And then, on the way home, while remembering all the jokes, I'm thinking to myself "Oh shit, that's smart".

Hades is definitely one of these.

Hades cover art

Hades, a supergigantic game

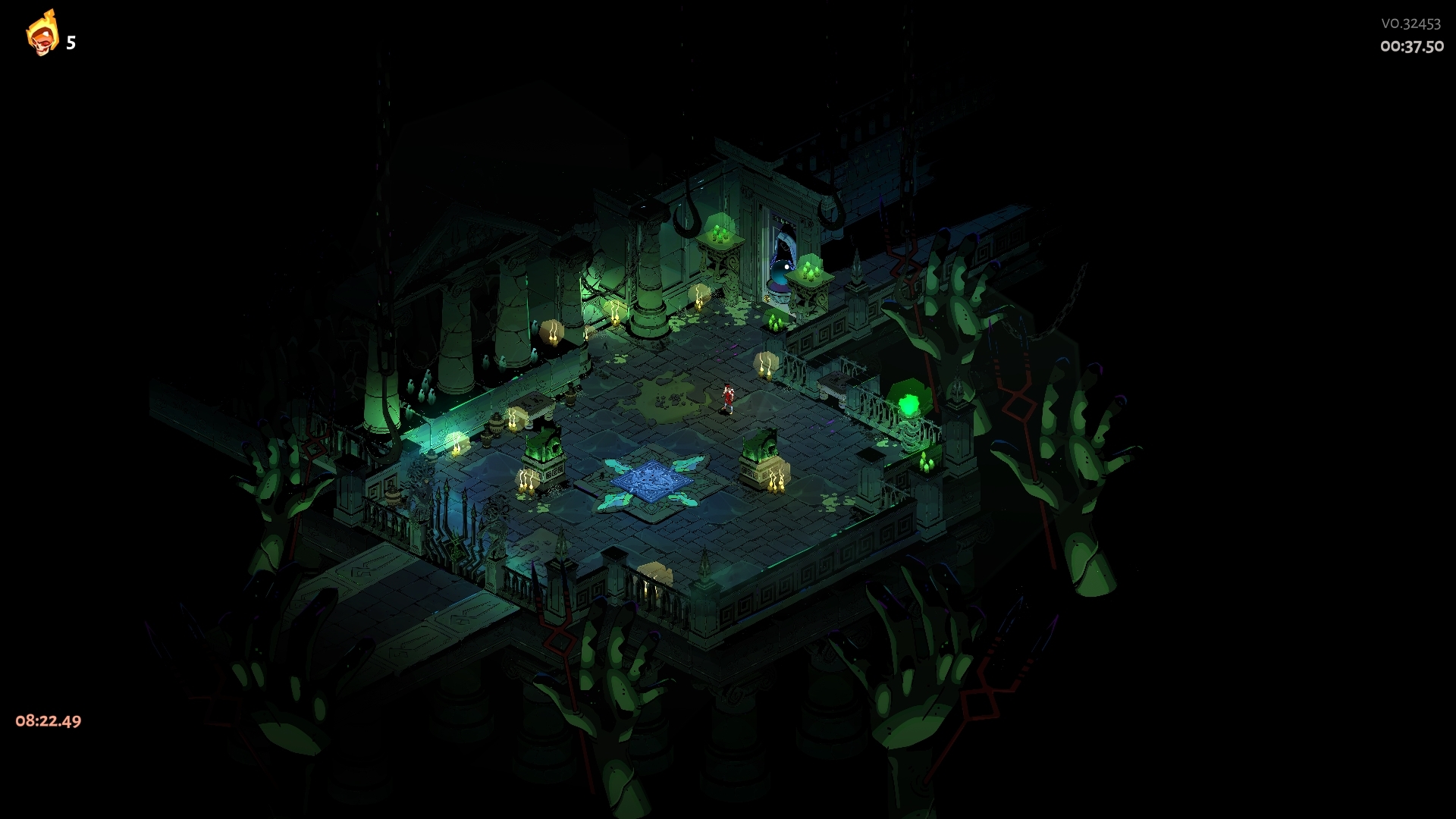

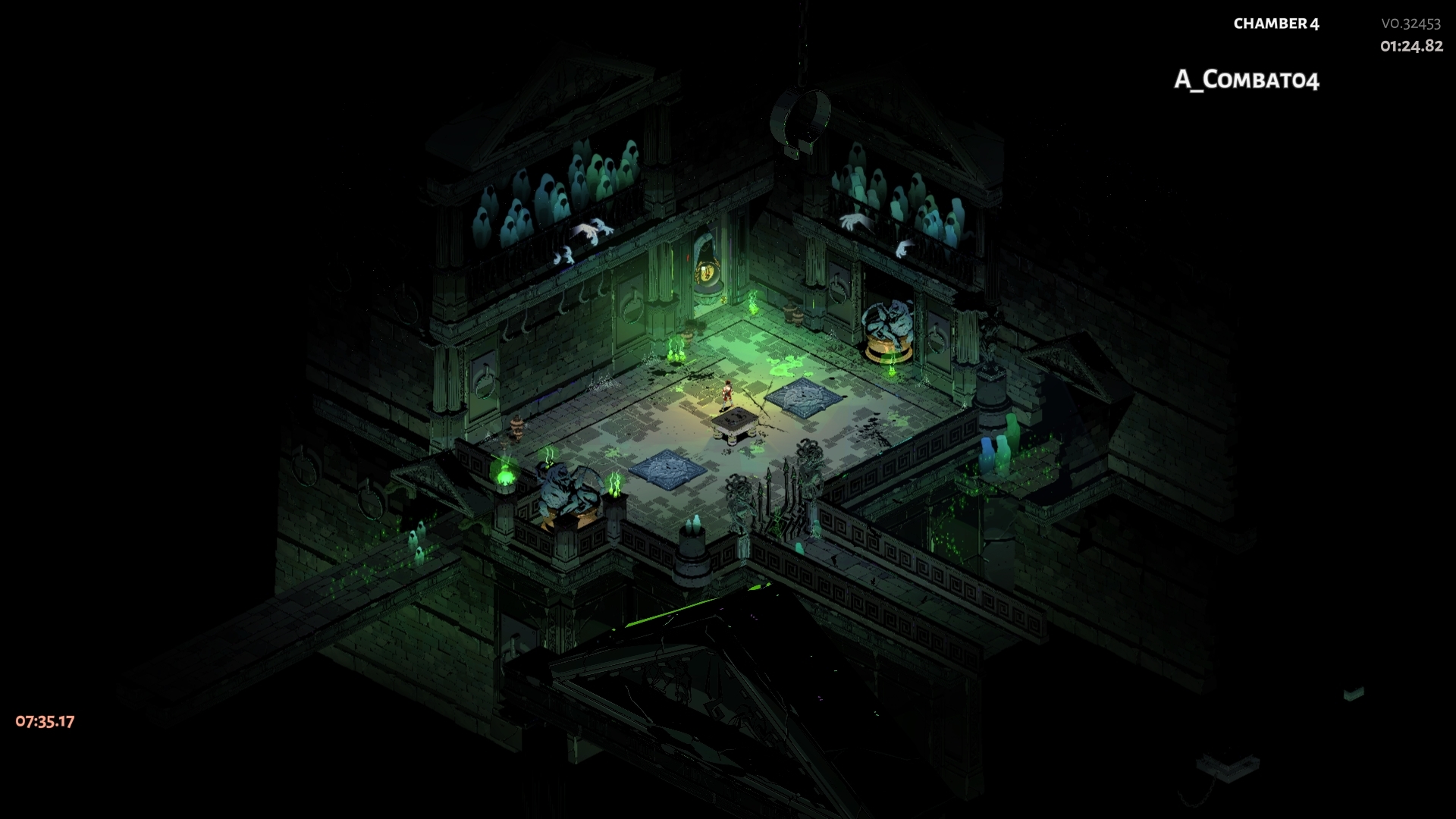

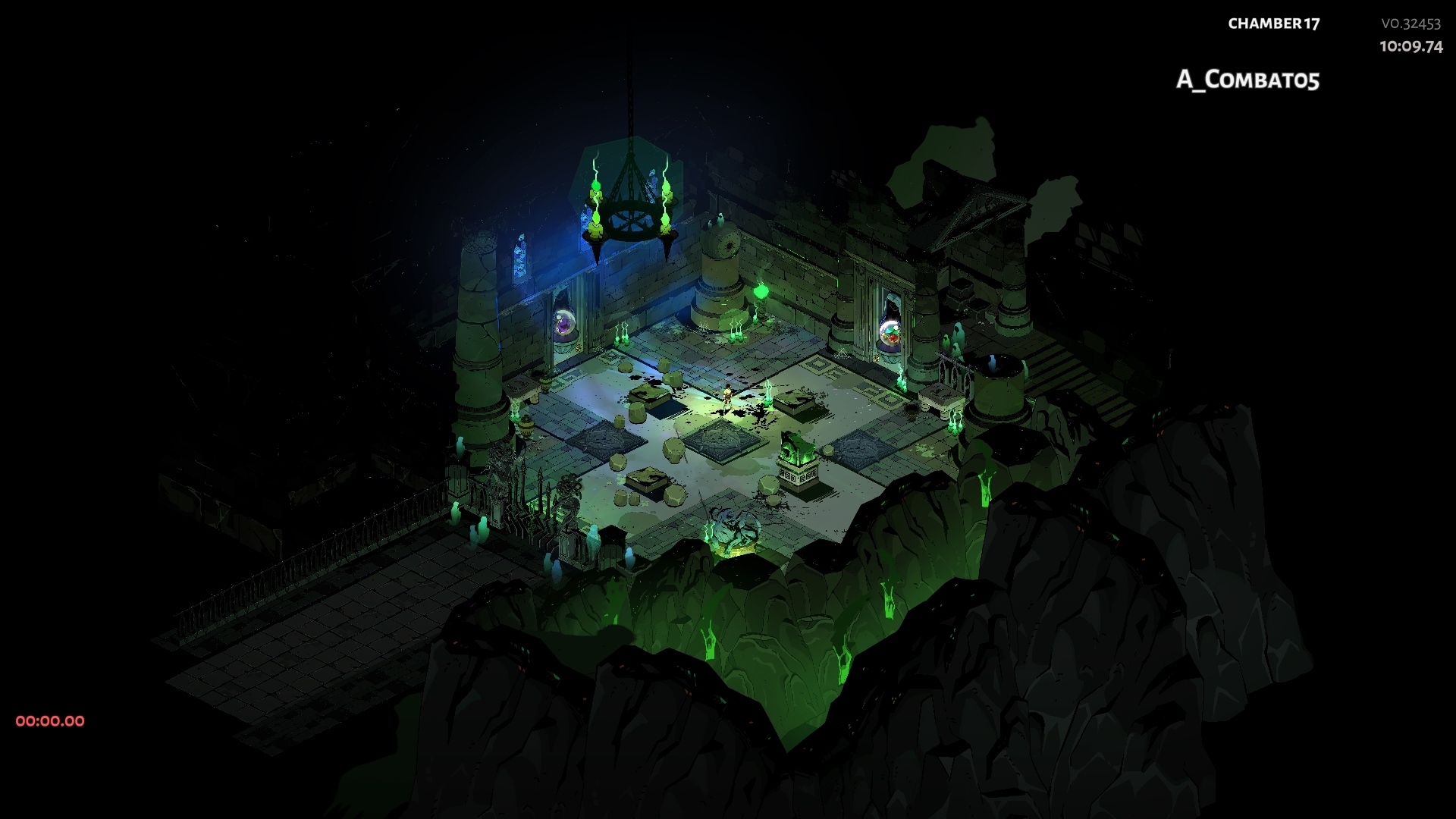

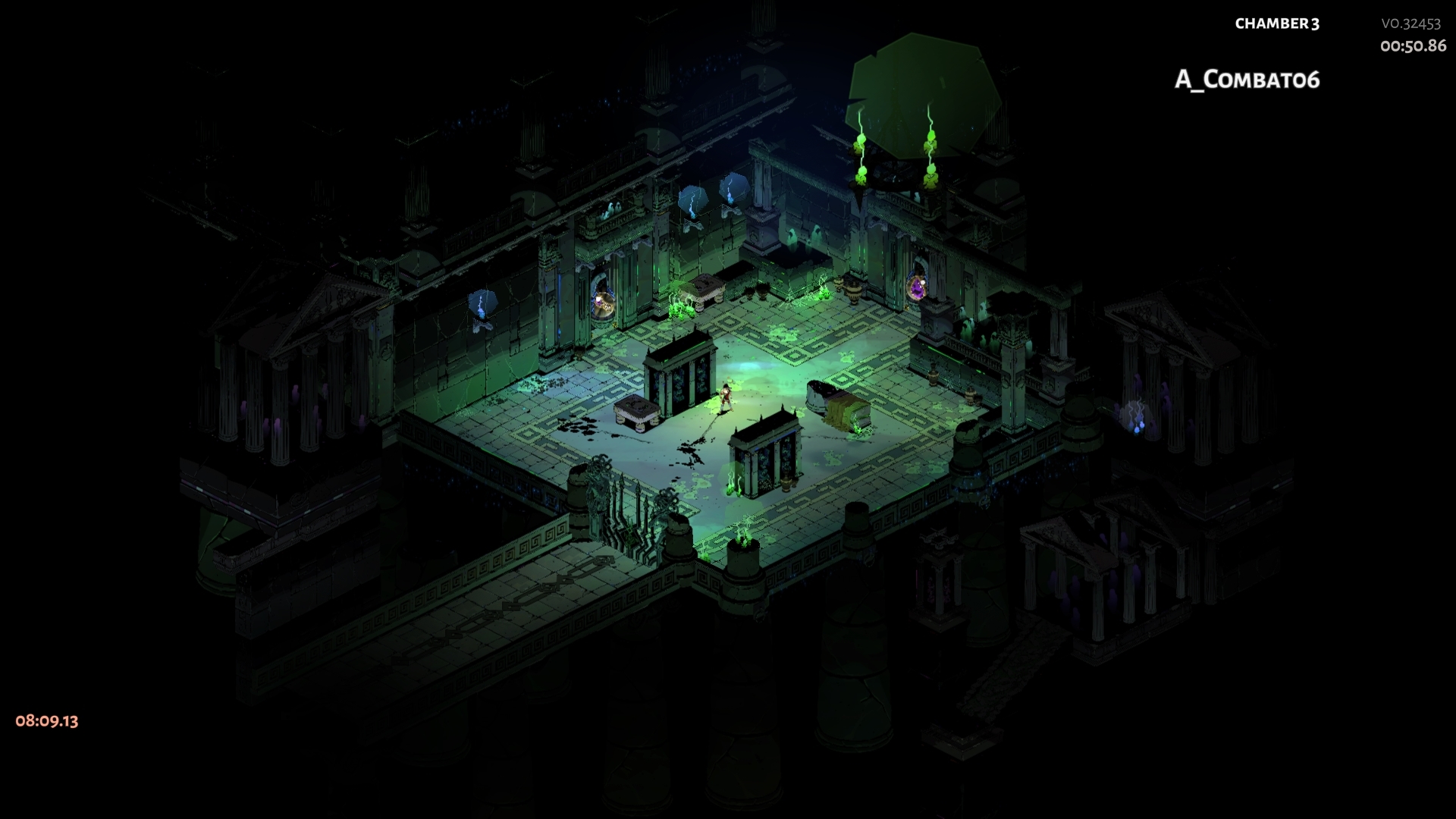

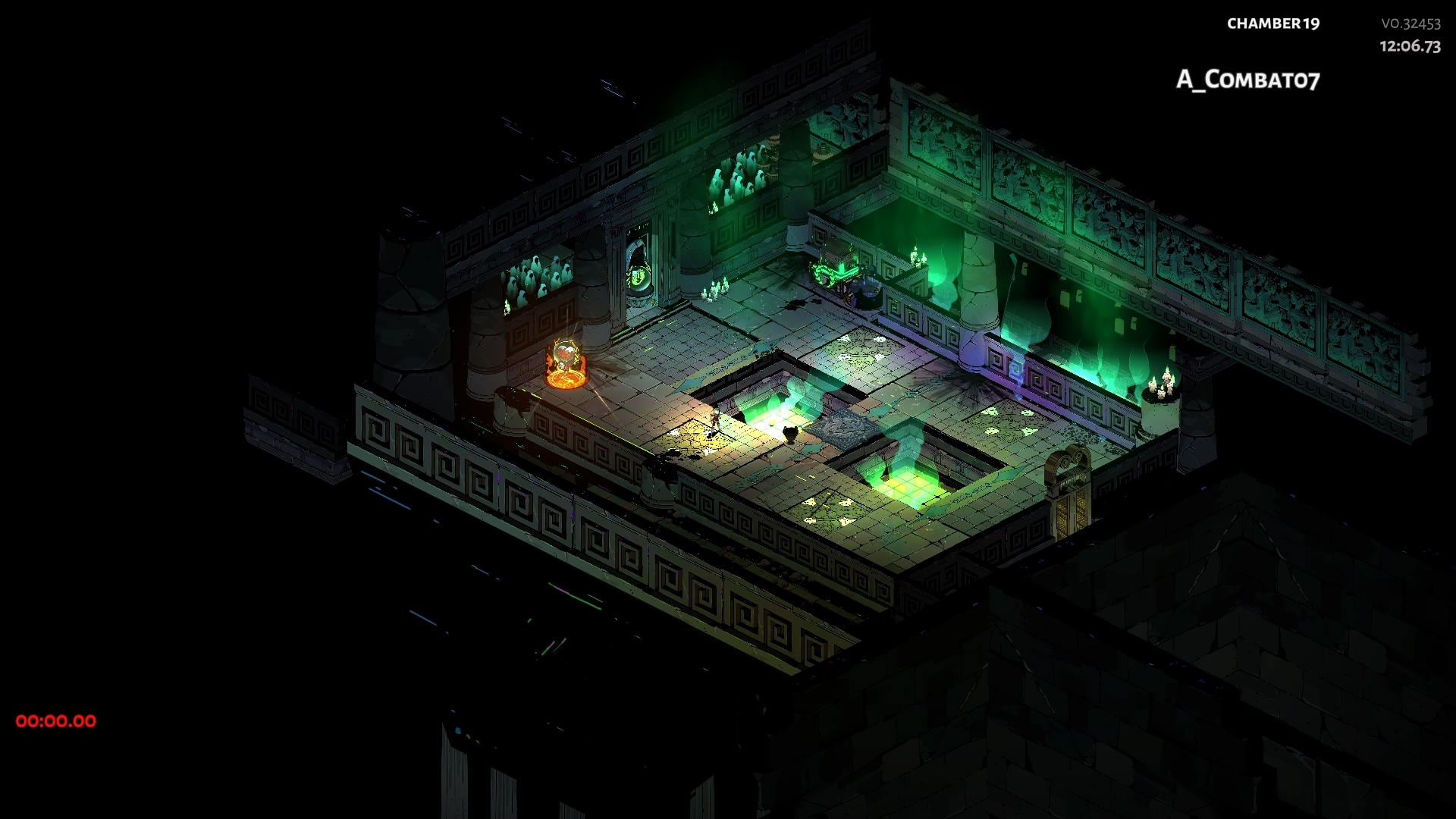

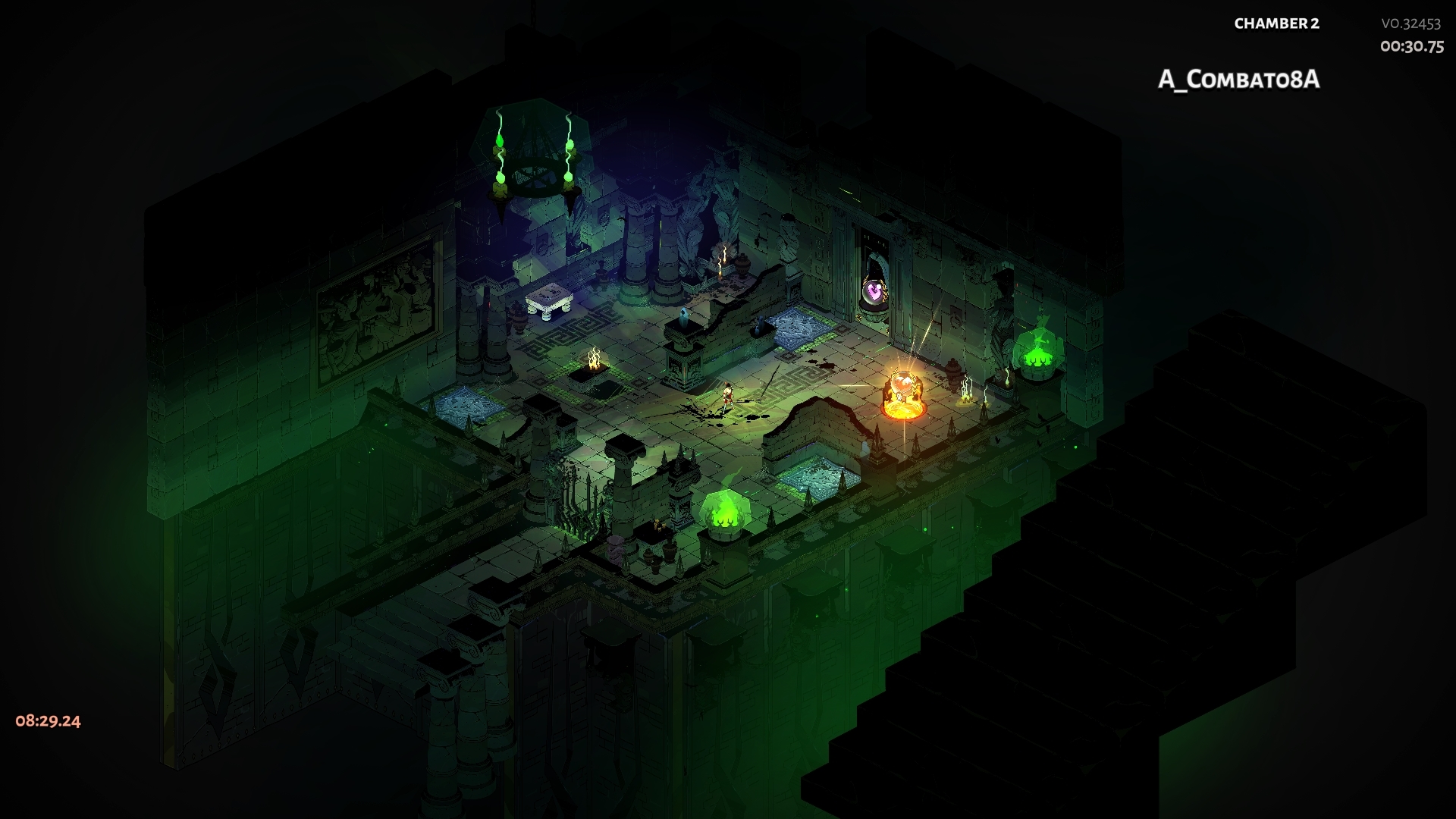

Hades is a roguelike where you embody Zagreus, son of Hades, while trying to break out of a eternally changing Hell (to not say procedurally generated). You can choose a weapon from your arsenal for each run and receive boons, abilities and powers from the gods of Olympus, to build up Zagreus' power during the run.

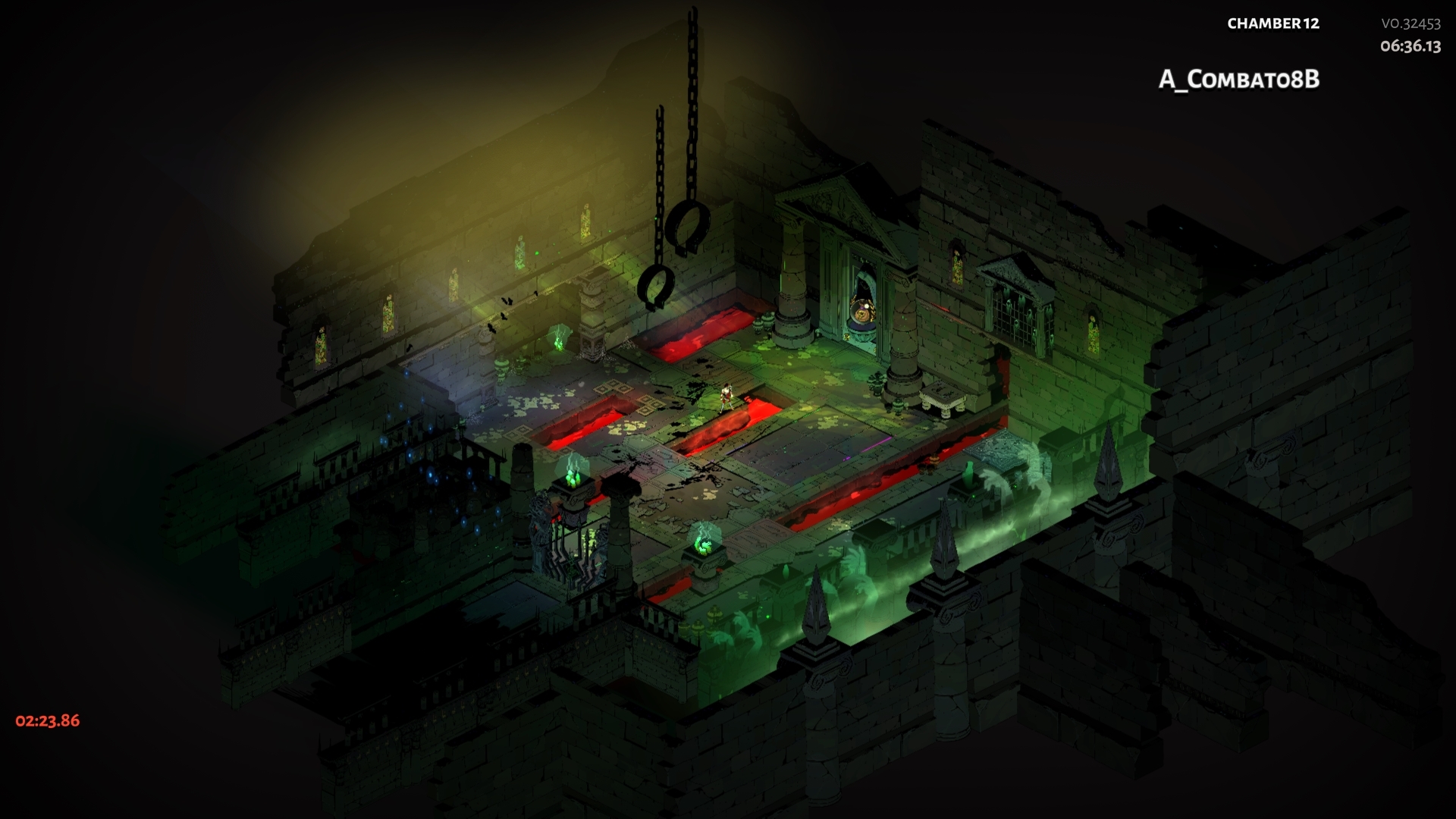

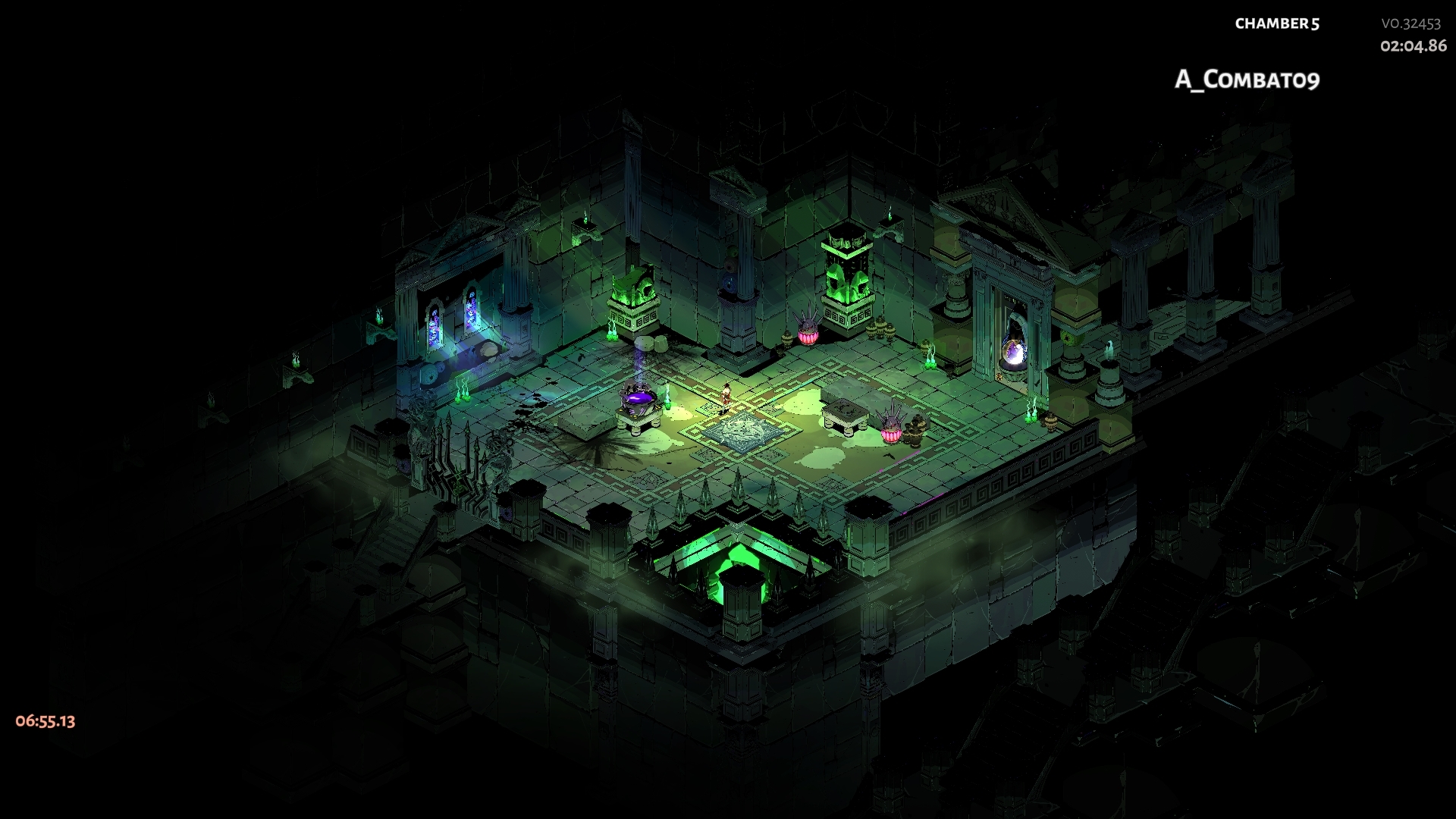

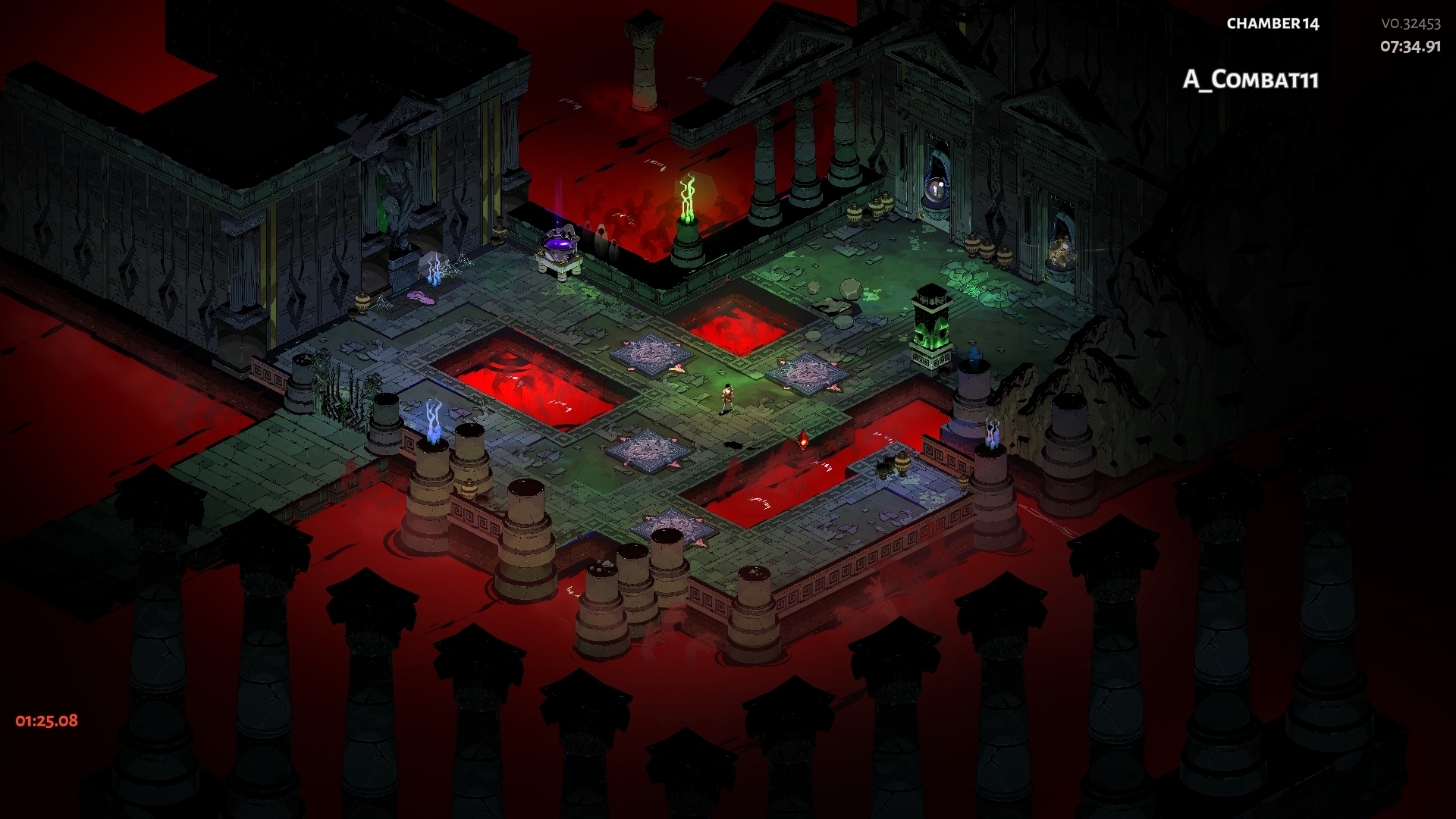

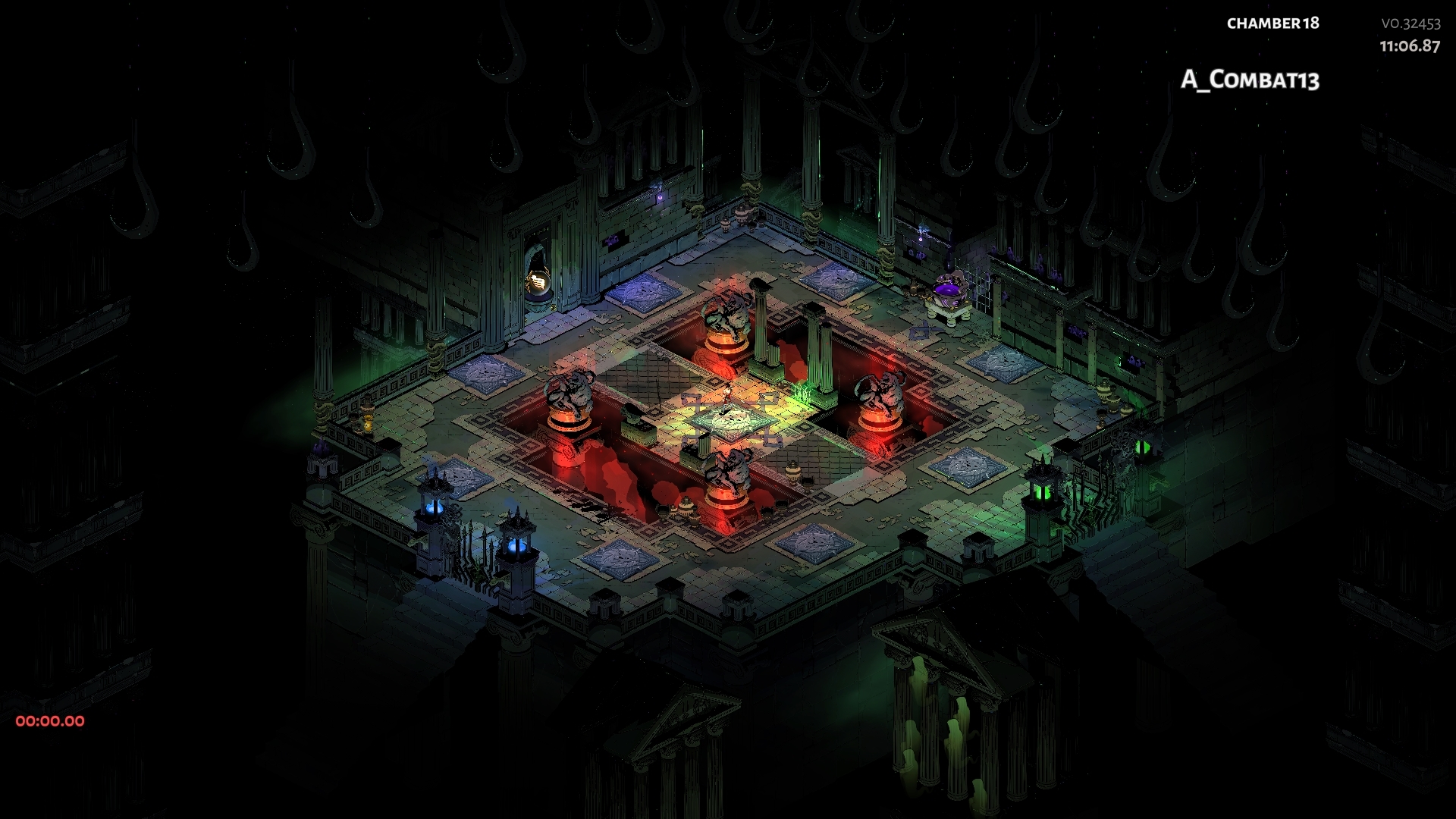

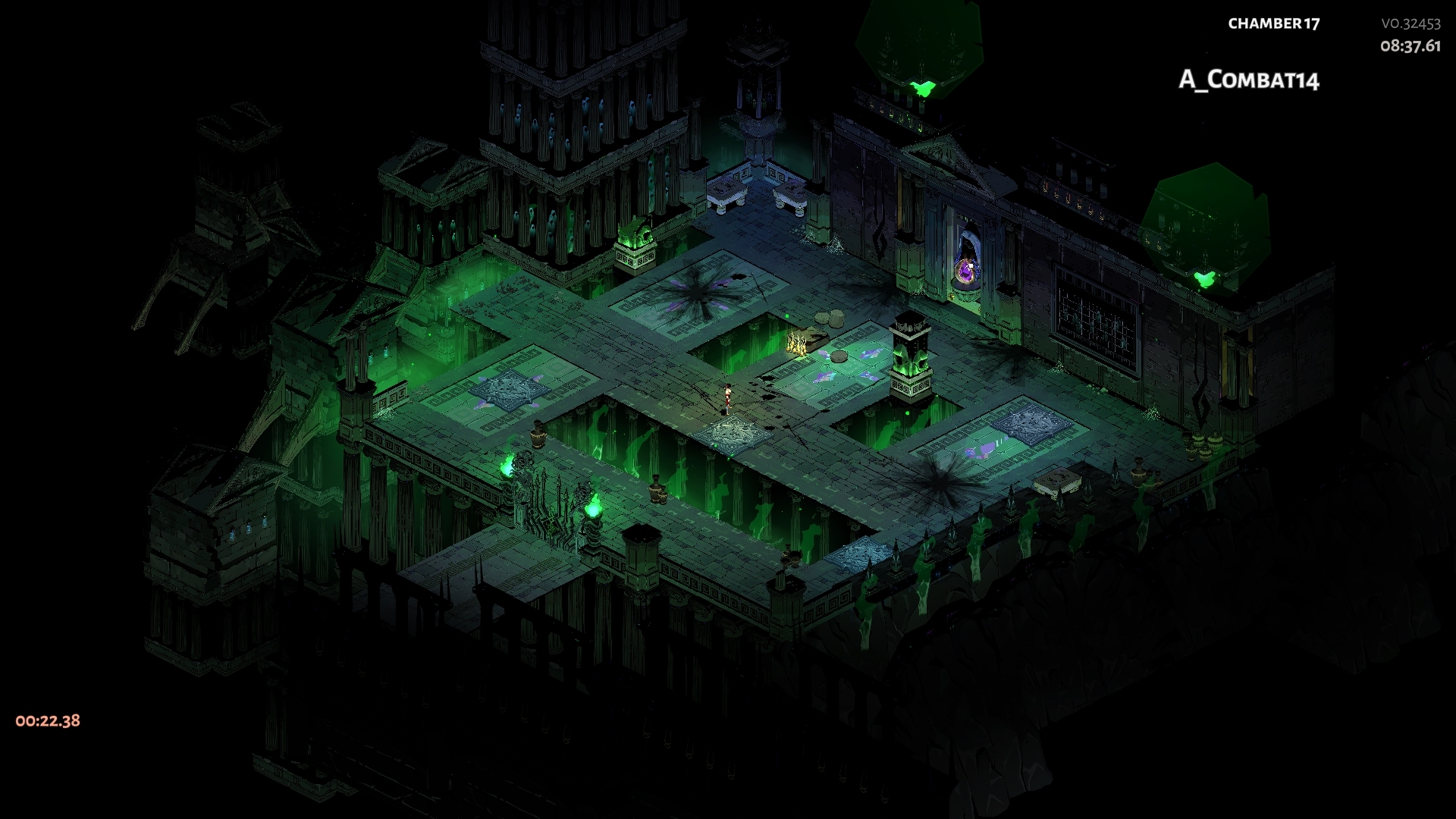

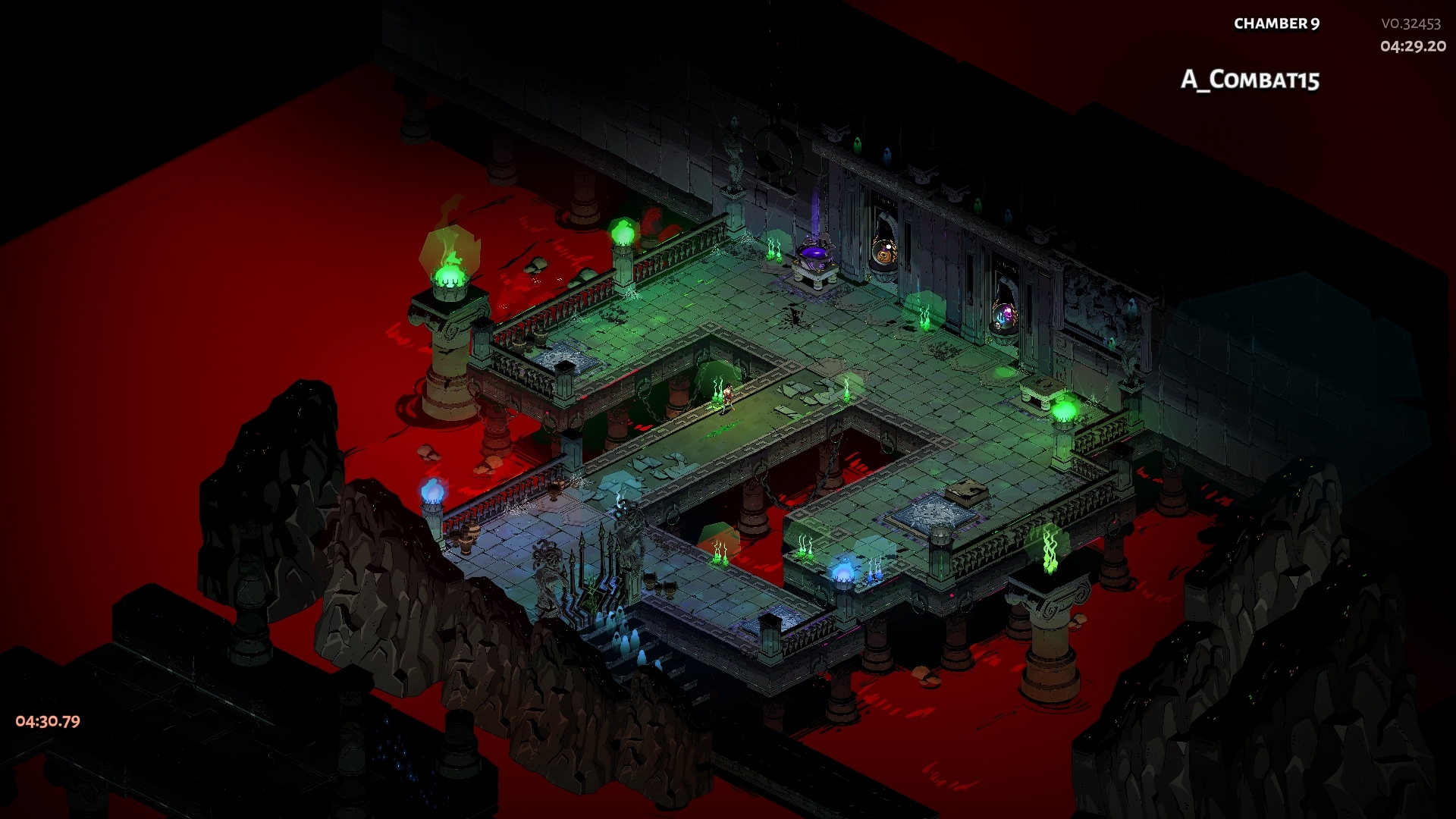

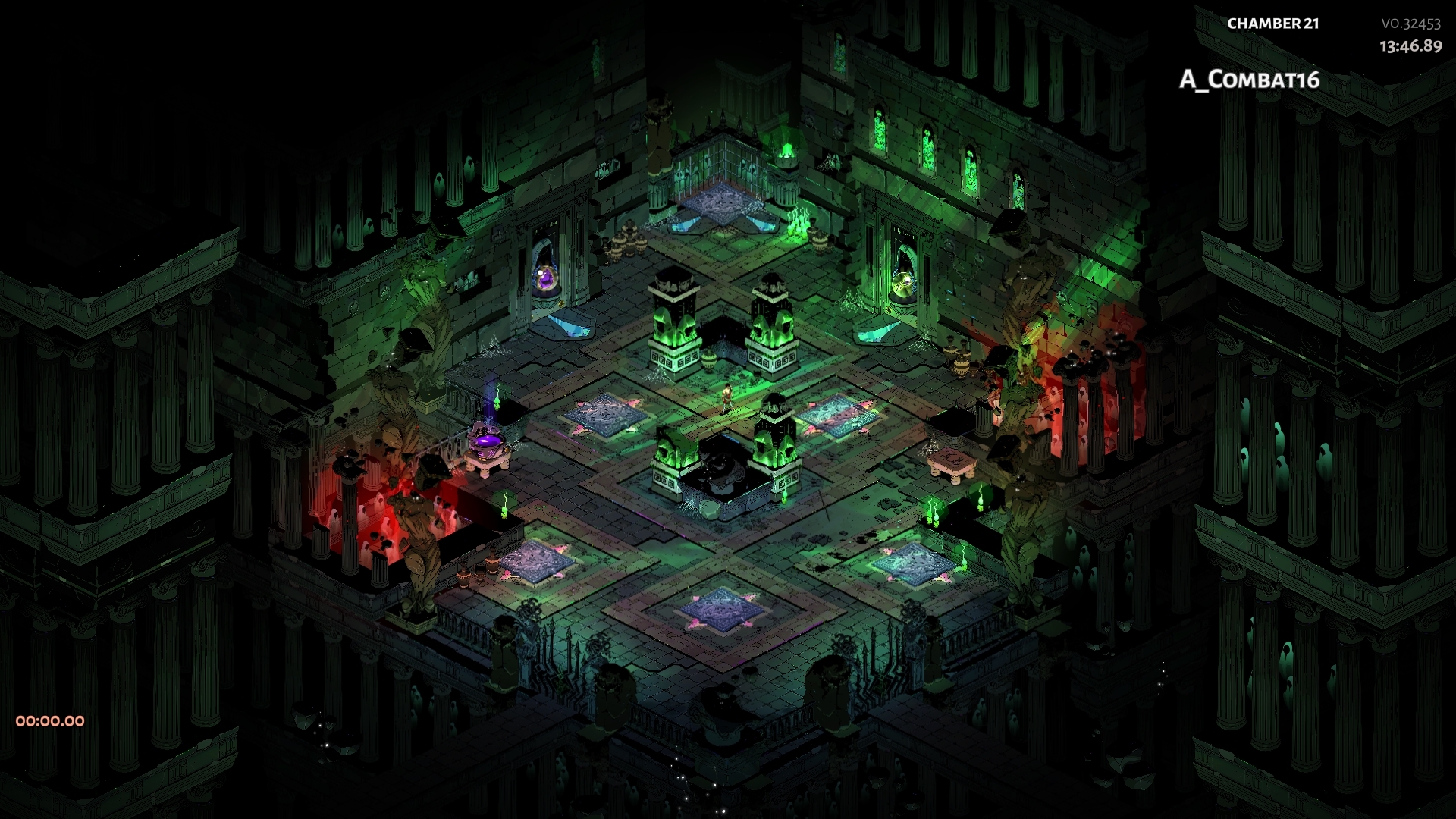

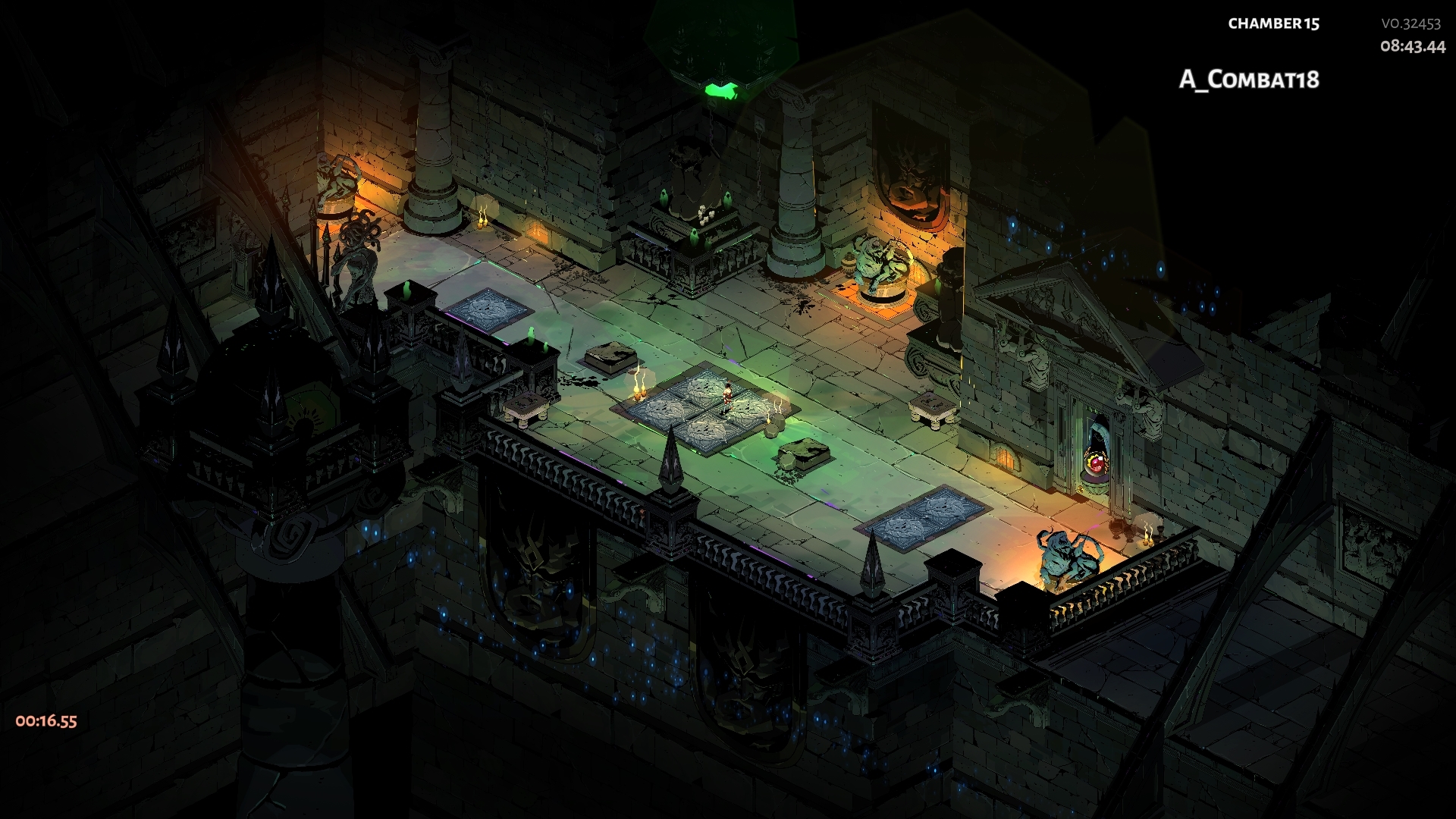

Hades uses an isometric view, with Zagreus on the center of the screen.

Hades is a phenomenal game that shines in every department: it is a blast to play its combat, a joy to marvel at its art, a pleasure to dive in its narrative.

Wether you like roguelikes or not, you should play Hades. And this article spoils a large part of its game systems, so I strongly advise you to play it first.

Hades is game made by Supergiant games, the team behind Bastion, Transistor and Pyre. The team grew from 4 developers at the time of Bastion to nearly 20 for the development of Hades, and that growth was followed by larger and better games. And if I emphasized the adjective larger, it is because Supergiant games are always very generous when it comes to the content of their games.

Hades is a very large yet super polished game, pushing the standards of the industry altogether (so much that its relatively low price at 20€ was a subject of heated conversations in the indie community).

Official Animated Trailer for Hades

Being a roguelike, Hades is focused on replayability: each run must be new, yet using the same grammar so that the player can still learn the game and get better at it. Procedural generation is essential to both the design of a roguelike (to keep things fresh yet familiar) and the production team.

You want to create a game with an infinite amount of runs,

with a very finite amount of time and resources.

Scoping this kind of project is a tough task, so let's crunch some numbers!

The size of Hell

On of the biggest task to tackle in a videogame like Hades is to create its world. Supergiant has a lot of experience in that matter, and were extra smart about designing their own version of a procedural Hell.

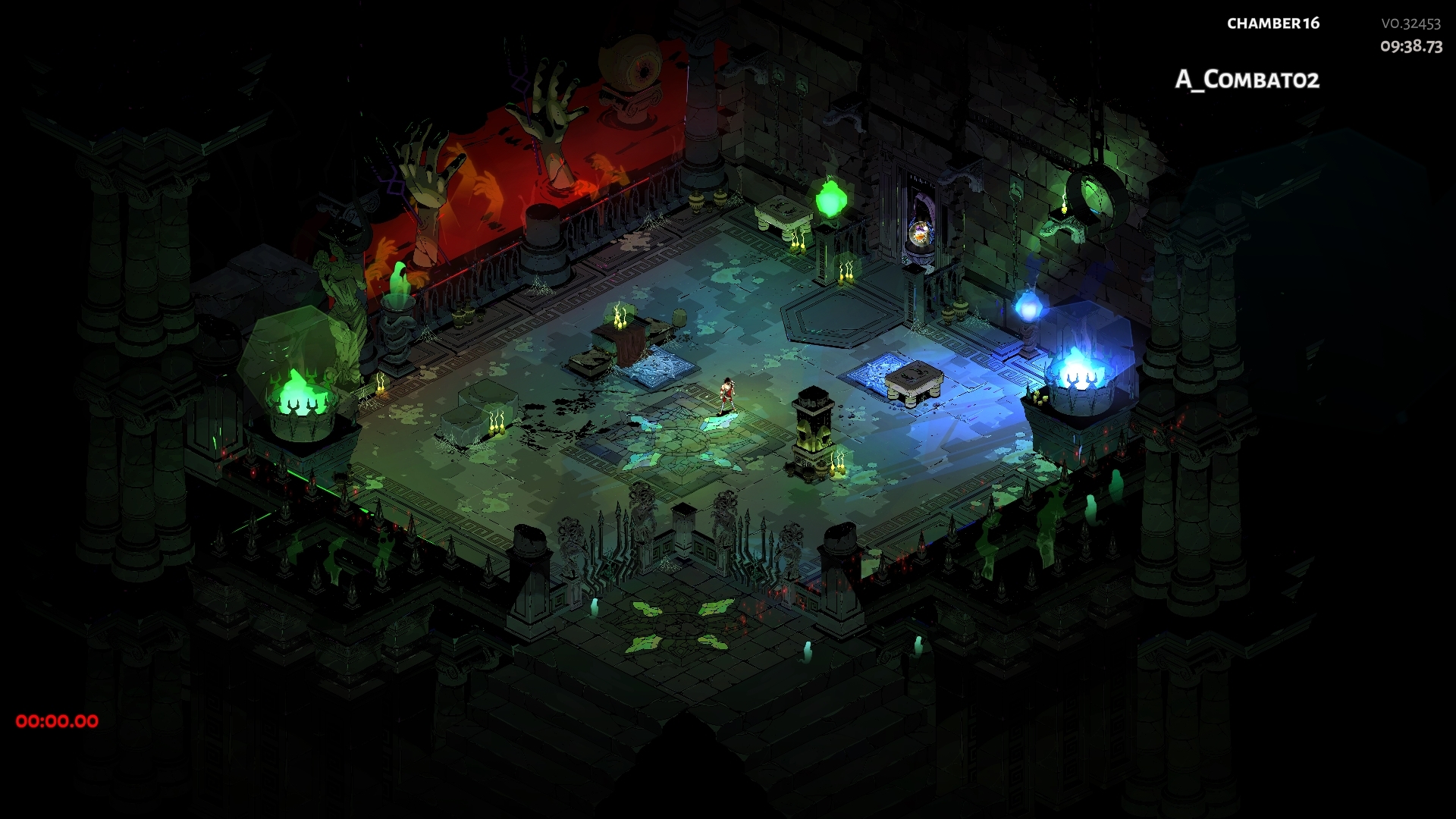

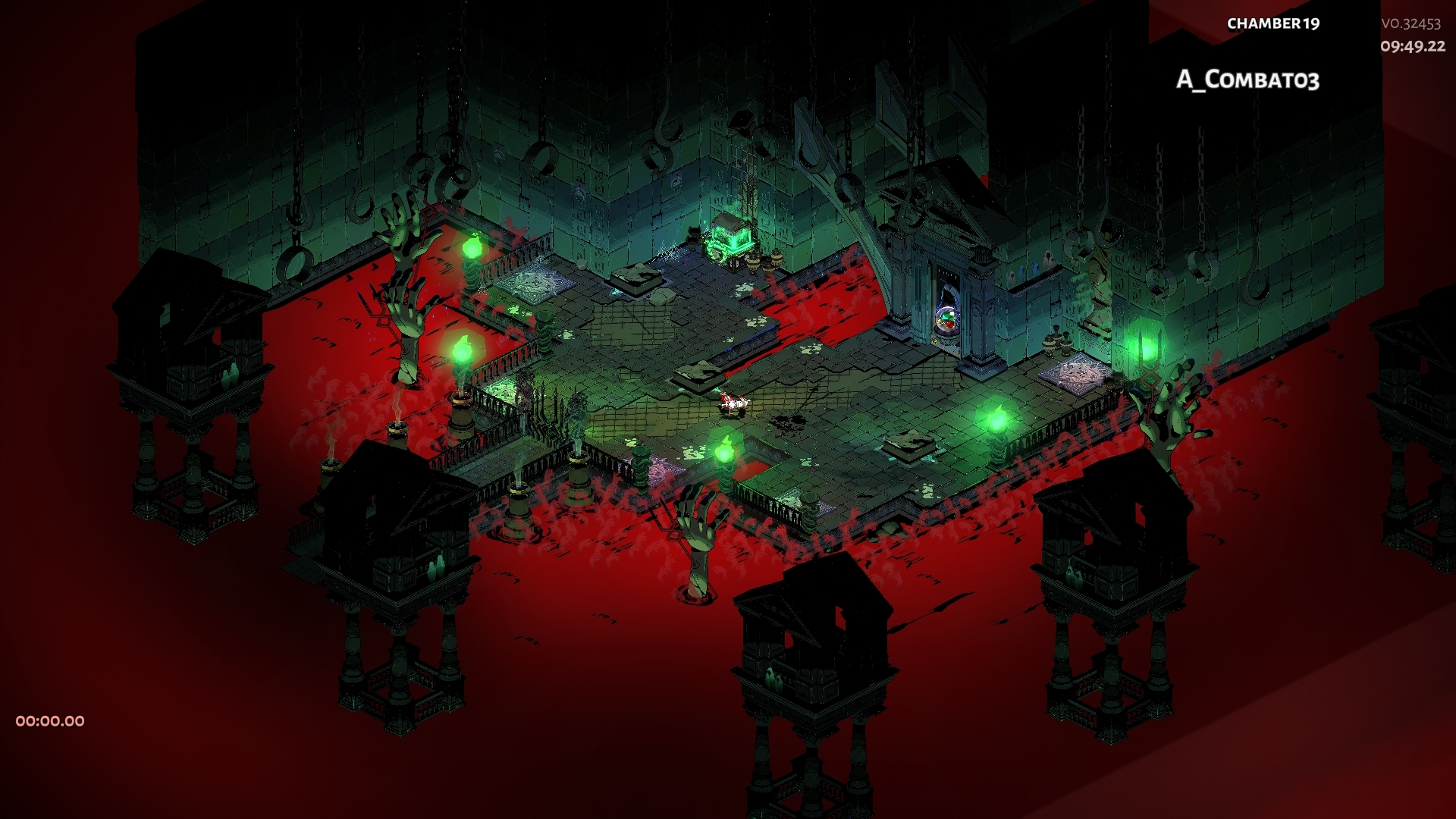

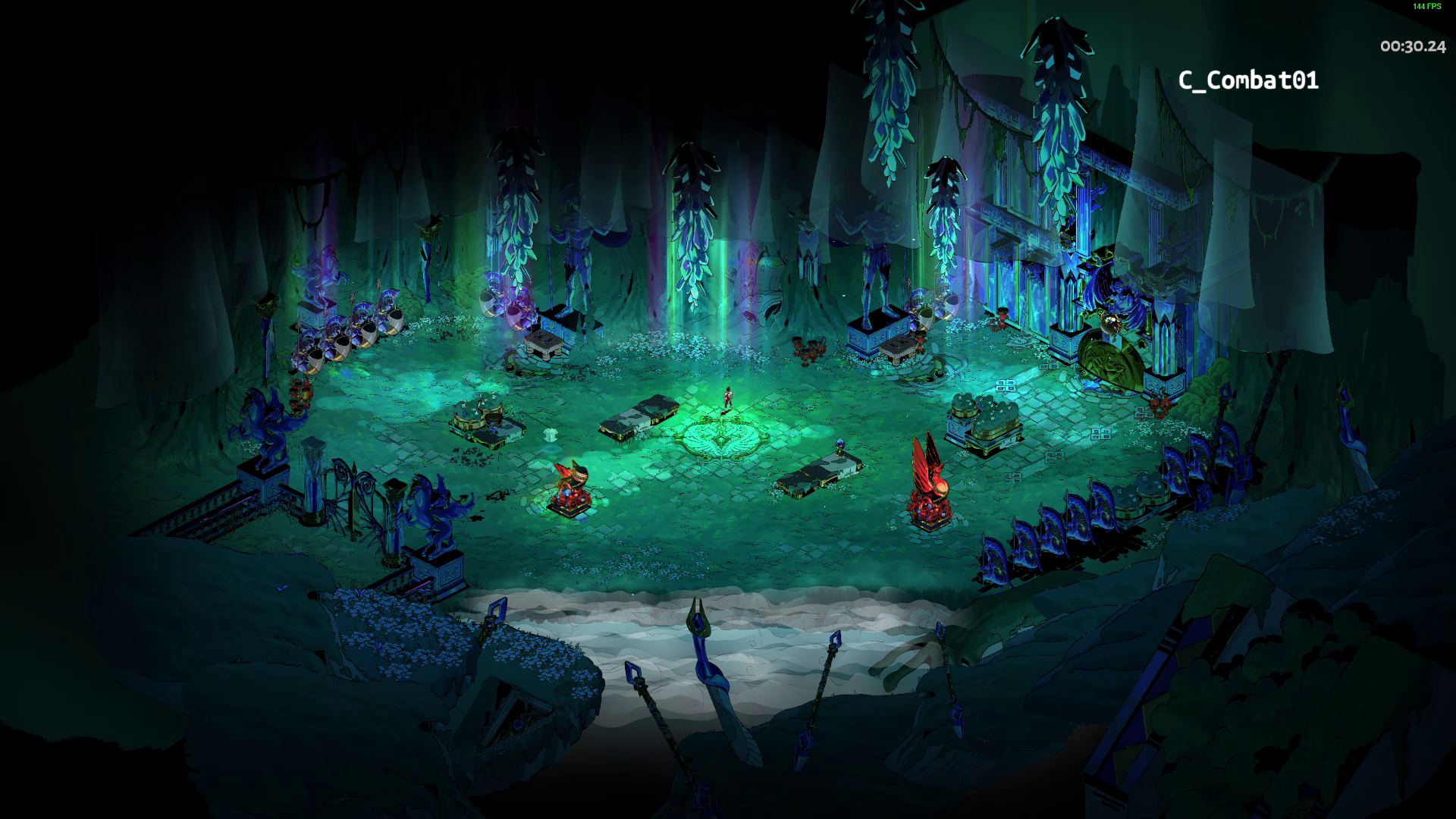

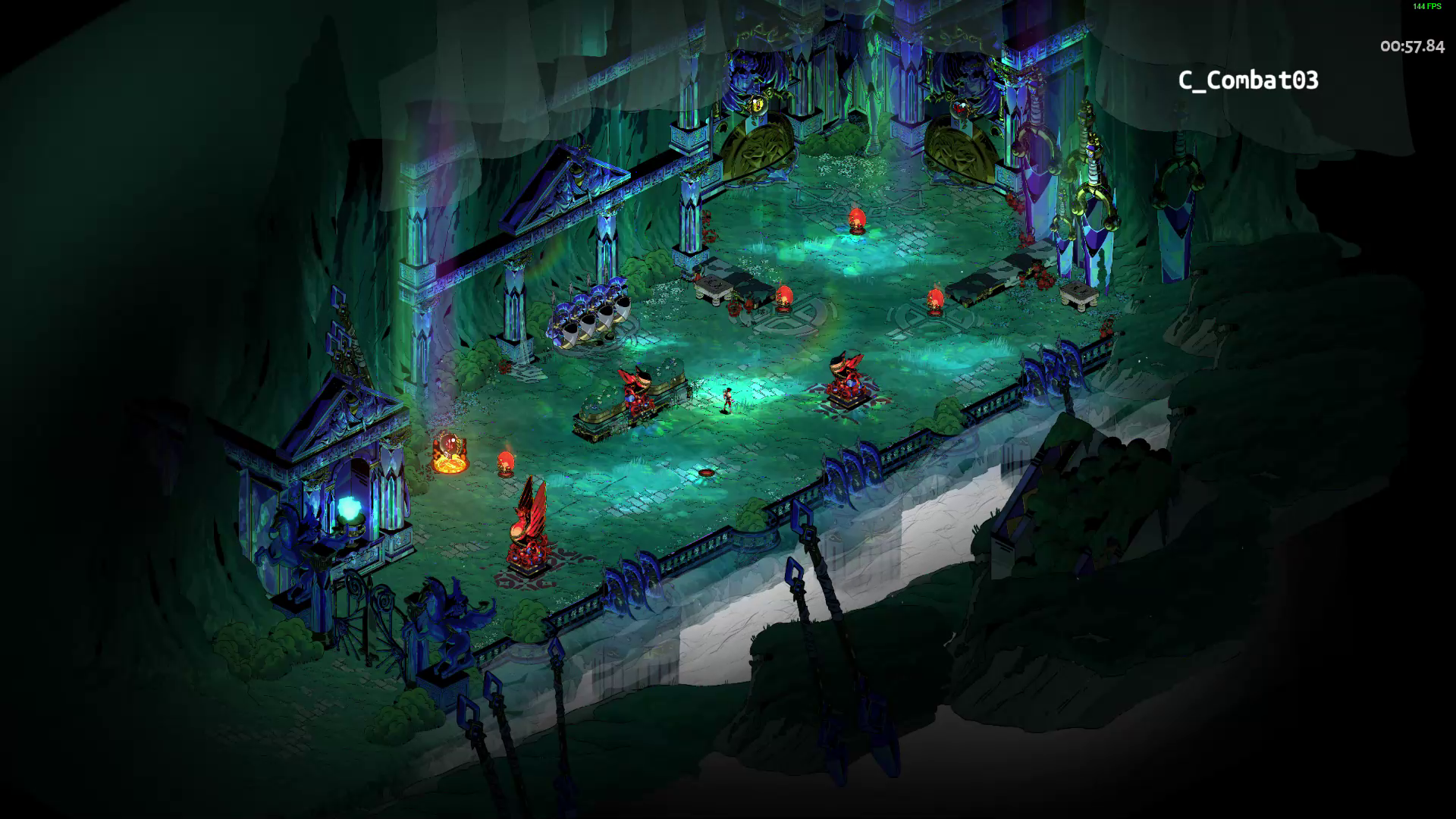

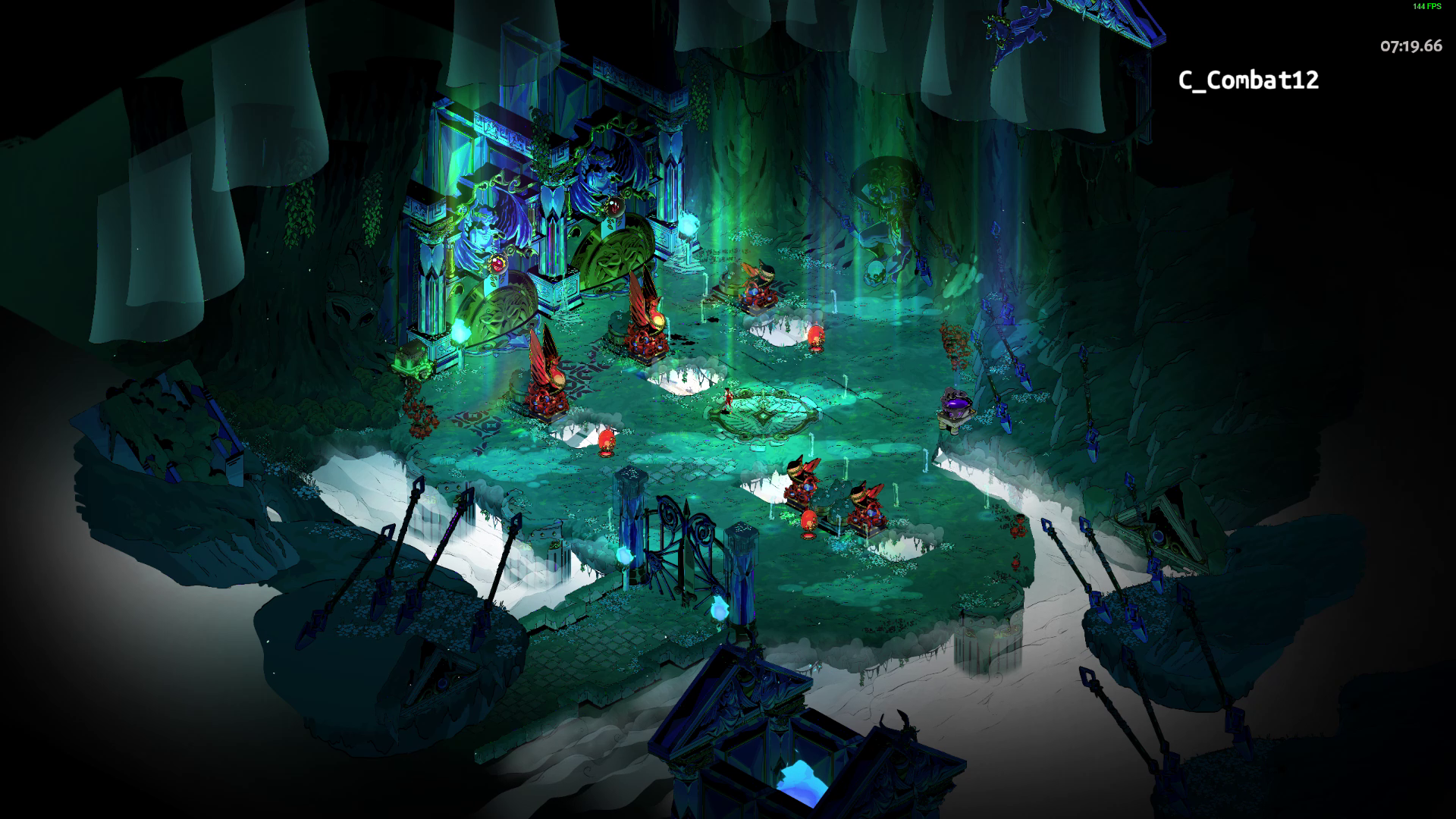

The player explores the world by stepping into a succession of rooms across 4 biomes : Tartarus, Asphodel, Elysium and the Temple of Styx. The room before each biome is a boss room, containing a particularly tough but constant challenge, the boss itself and the layout of its room remaining unchanged across runs (well up until the endgame starts). What does change in each biome is the rooms you cross before the boss.

Supergiant is using a technique I described before as content distribution : Hell is not redrawn from scratch every time Zagreus steps into Tartarus yet again, Hell is pulling rooms from an existing library and linking them with doors.

This technique is great because it automatically gives you a distributed design process split in two layers : designing individuals rooms and designing the rules of assemblage. Even then, it doesn't mean that it becomes easy: it will take many iterations to nail the level design of the rooms, artists will spend days preping every room into looking gorgeous, a programmer will write and rewrite dozens of times the algorithm of generation.

Here are the standard rooms of the first 3 biomes (source):

24 rooms of Tartarus

11 rooms of Asphodel

13 rooms of Elysium

The number of rooms you will cross in those 3 biomes is fixed for each run :

- Tartarus starts in chamber 1, ends in chamber 12 (13 is the end shop).

- Asphodel starts in chamber 16, ends in chamber 22 (23 is the end shop).

- Elysium starts in chamber 26, ends in chamber 34 (35 is the end shop).

For Tartarus, that means that we have to pick 12 rooms in our 24 rooms library.

In this context, how many different Tartarus configurations exist?

Since the order of the rooms is important, the combinatrics boon we are going to use is permutation, an ordered arrangement of elements.

More specifically, we are trying to count the arrangements of 12 rooms taken from a set of 24 rooms, so we are talking about the k-permutations of n, where k is 12 and n is 24.

To discover the formula giving us the answer, we have to think of what happens when we are generating an arrangement. We start with our n rooms and the first thing to do is:

- Choosing our first room. I have exactly n choices at this point. So I'm choosing a room at random and taking it out of the library.

- Ok so now let's choose a second room. I have n-1 choices now, because I can't choose the element I picked as the first room.

- On the third room, I will have n-2 choices, because I can't pick the first two elements.

- You get the idea: on the room n°X, I will have n-(X-1) = n-X+1 choices.

- On room n°k, I will have n-k+1 choices.

The final number of arrangements is the product of the possible choices at each step. Thus: .

And this formula can be simplified with factorials like this:

is the number of rooms to choose, is the total number of rooms

So in the case of Tartarus:

In the case of Asphodel:

In the case of Elysium:

Just for the first biome, we have a number with 16 digits. And the situation is even more crazy since each chamber can be mirrored, each chamber can welcome different challenges, each chamber can contain or not chests and pots. And I don't count the special chambers or internal mini-bosses in the mix. In any case, the real number of arrangements is of course higher.

With those kind of numbers,

a player will never pass through the same version of Hell.

You can set up your own numbers and calculate the number of arrangements directly below (until it goes over the maximum integer authorized by JS):

n =

10

k =

5

I find this calculus fun for hero-based arena games, like League of Legends or Rainbow Six Siege. The roster of the characters is often huge, theoretically offering unique combinations each game.

Plot twist: these numbers are stupid

I didn't present all the systems of Hades that introduces differences for each run: the mirror of night, the weapons, the keepsakes, the boons, ... with everything combined, this game offers more than billions of billions of variations.

And now, the hard truth:

The mathematical variations are not game design variations.

The numbers I developed do not represent the variety feel of players in Hades. It doesn't mean that it's completely useless, it means that we need to reinterpret them a bit. And my first argument is:

The majority of mathematical variations are insignificant

The size of Hell doesn't matter that much because players won't make a huge deal out of the fact that they won't cross the same rooms in the exact same order as their last run. What is important for sizing Hell is how many rooms do I cross each time out of how many rooms exist, so the coverage of the set of rooms.

Tartarus picks 12 rooms out of its 24 choices,

so you'll see 50% of the library on each run.

Asphodel picks 6 rooms out of its 11 choices,

so you'll see 54% of the library on each run.

Elysium picks 8 rooms out of its 13 choices,

so you'll see 61% of the library on each run.

And that is by design: a roguelike like Hades rewards learning through repetition. If you step into a completely new room you're not gonna feel as in control as if you step into a room you crossed 50 times already. And like most games, Hades' players thrive on the power fantasy the game offers.

It's very logical that the % of coverage increases across the biomes: Statistically, you'll see Tartarus way more than Elysium, so it makes sense that Tartarus is more diverse. Another reason would be on the production side: Hades was in early access and the later biomes came in title updates, when you don't necessarly have as much cooking time as for the first biomes.

Striking a balance between variety and familiarity on the same game system is tough, that's why roguelikes found a neat technique : just make two game systems on top of each other. One is predictible (the dungeon generation) and you can learn it quickly, and the other is way more random so you can't predict its behavior easily (the character build per run system). This separation allows the two game systems to have more focused role while complementing each other.

Indeed, you want players to keep building their runs on the knowledge accumulated on the first system, enough to give them the confidence to improvise and try something new in the other system. The variety feel is created by the players themselves through their engagement in a complex system, made possible by their mastery of another underlying one.

No Man's Sky claims it has over 18 quintillion planets.

The 18 quintillions planets of No Man's Sky are meaningless if they all play the same. The 1 billion weapons of Borderlands 3 are meaningless if they all play the same.

Those huge numbers behind procedural generation hide the true depth of their game systems behind mathematical reasoning. Hades is great because many game systems introduces significant gameplay variations: the mirror of night, the weapons, the keepsakes, the boons, the pact of punishment, ... With just those, Hades can offer easily 1000 entirely different runs, when 99% of players won't go past 100.

Conclusion

Like any scientific measure, sizing your game systems must be analyzed and put in context. A big number doesn't necessarily mean big in-game value. And that's what I find fascinating about game design: its defiance towards mathematical logic.