Designing information: why is it hard to communicate science

Questioning the place of science in our current culture and the stakes behind its popularization.

Introduction

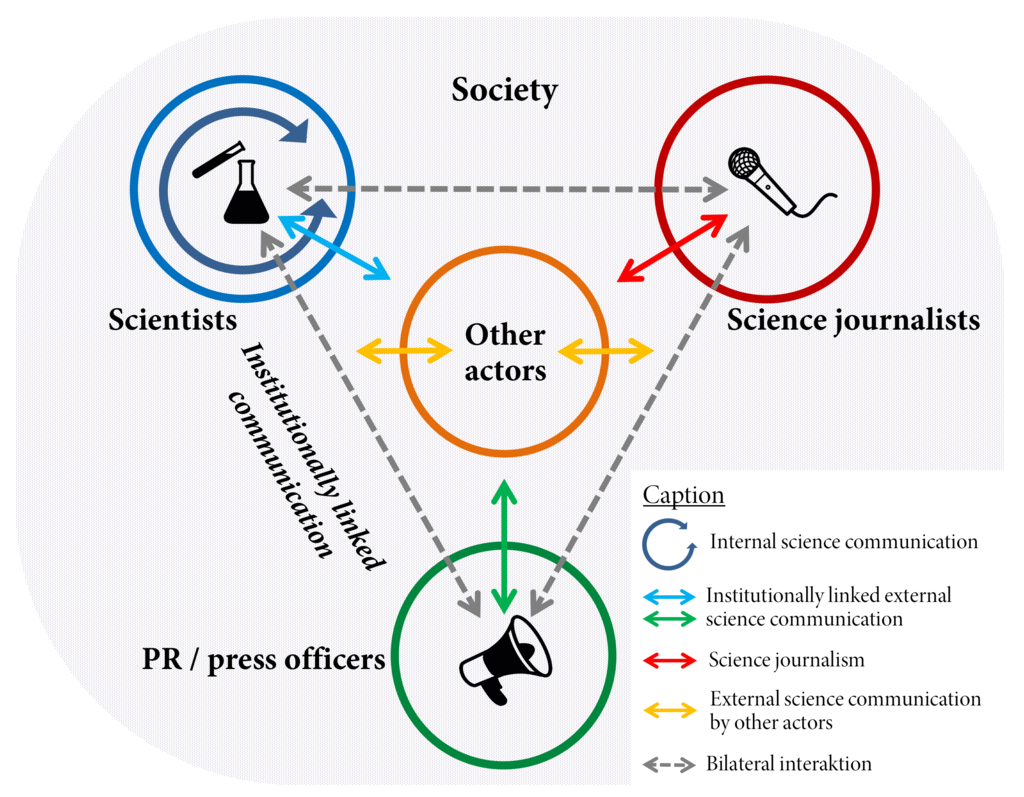

Schematic overview of the field and the actors of science communication according to Carsten Könneker (Source: Wikipedia)

Almost ironically, science has always been a cornerstone for culture. The best proof for that would be science-fiction : an entire genre of art and creation mainly in literature and cinema based on scientific facts or theories to build entire worlds. It was the spectacular inventions of the XIXth century that inspired Jules Verne to write marvelous adventures, it was the madness behind the growth of technology that inspired Philip K.Dick to imagine dark futures.

The last two centuries has more contributed to scientific knowledge than the last five millenniums, advances are made everyday in multiple domains around the world even without our knowledge, me writing this piece or you reading it. It has been a real challenge for education to digest this knowledge and transmit it to new generations, through courses of course, but also through more accessible content. The Universal Exposition was a way to show and explain scientific wonders to a large public, science tv shows were ubiquitous at the birth of TV, documentaries have developed rapidly in the world of cinema. However, all those initiatives are insignificant compared with what the Internet did for scientific knowledge. All the sudden, knowledge and information from all over the world was accessible, readable, editable, creatable. Wikipedia is the quintessential product of this incredible flow of knowledge travelling through the web.

However, the incredible flow of knowledge is not necessarily good knowledge: it’s not because Internet “says” it that it’s true. The problem is that the quantity of information flowing at each second is beyond anything that one can control, and as one saw with the recent political events, “fake news” are spreading very easily on the social media landscape. These fake news could be about anything but are often using fake science to appear as an authority and thus be trustworthy.

In this paper, I will try to analyze how to communicate science and especially why doing it in a better way is essential.

Communicating science today, how?

Teaching is absurdly hard. Yet, educating everyone on science matters and issues is essential to the evolution of mankind. Teaching may be difficult, but it is crucial to succeed. For what one call “natural sciences” (mathematics, physics, biology mainly), the task is huge. Milleniums of knowledge must be condensed into something understandable and able to serve as a base for more science to grow on.

On this subject, one may think of Nicolas Bourbaki. Nicolas Bourbaki is a false mathematician, created by a eponym secret association of french mathematicians in the 1950’s. Their goal was to write maths books that compile all the mathematics knowledge at the time with a clear structure and internal logic and a uniform writing style.

Cover for 'Elements of Mathematics : Set Theory' (Source: Wikipedia)

After many years of preparation due to their endless debates, their “Elements of Mathematics” changed the teaching of mathematics in the whole world, and today, everyone math book still uses (more or less) the Bourbaki method. Either if it's still relevant today or not is a debate for another time.

Beyond the transmission of knowledge, teaching is also about the transmission of the interest/passion to the students. Curiosity is the main engine that drives one’s learning and since high-level science is basically a huge pile of complicated stuff, it is important to suscitate curiosity and fascination around it, to motivate people to gain that knowledge.

And here begins the story of science popularization, with the not-so-easy task of bringing scientific knowledge to the masses, to spark curiosity in their hearts but that’s probably too dreamy. Science popularization is basically explaining the simple stuff in a fun and accessible way. Teaching can be popularization but popularization is not teaching. A popularization program is much shorter and is generally less accurate than a true lesson.

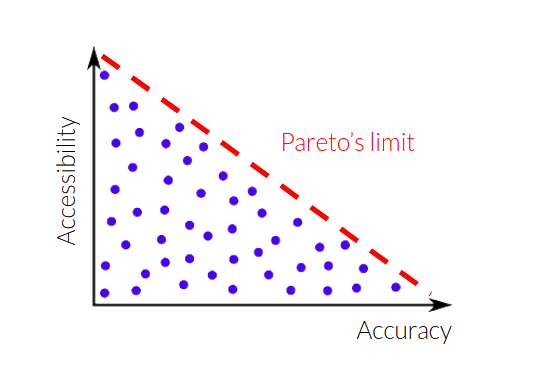

Thus, a science popularization content is constantly balancing between accessibility and accuracy. One can’t be perfectly accurate and perfectly accessible : you are limited by the Pareto’s limit.

On this graph, each blue dot is a science pop. video for example. (Source: ScienceEtonnante)

In a famous BBC interview, when Richard Feynman is asked about magnetism, why two magnets repel each other, he admits not knowing how to answer the question. Not because he doesn’t have the knowledge - he was probably the greatest erudite in physics at his time - but because he doesn’t know his public : “When you explain a “why?”, you have to be in some framework that you allow something to be true. Otherwise you’re perpetually asking “why?”.” Thus, your position on the graph essentially depends on your target, not on you.

I beg you to watch this entirely.

As a consequence, science popularization is always hiding information : it is lying. BUT it is the truth in a certain framework, not a certain opinion, and most importantly it doesn’t contradict or betray the ground truth.

If science tells the truth, why is it so difficult to communicate that?

You realize now that, even with science communication, the notion of truth is tricky : it is always a truth, based on the context of the communication, on the public, not necessarily the whole truth. This makes science communication difficult for those who are not used to it. In addition, a strong psychological effect is playing its part here : The Impostor syndrome.

The impostor syndrome is a psychological pattern in which an individual, in this scenario a scientist, doubts their accomplishments or their knowledge, convinced that they are not rightful to talk about their science specialty. They focus on all the things they don’t know, instead of seeing all the things they can actually explain very well.

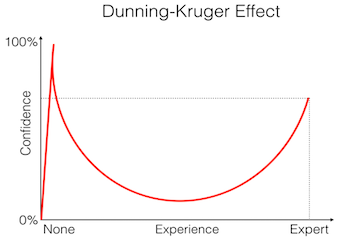

On the contrary, for non-scientists, another psychological syndrome can influence them : the Dunning-Kruger effect. This effect actually englobes the impostor syndrome but is more known for the following tendency : an individual with low ability or knowledge on something will often think having illusory superiority and will mistakenly evaluate their true expertise on something.

Pic of stupidity early on, the valley of despair i.e. impostor syndrome and the slope of enlightenment (Source: Catalog of Bias)

The basic application of that effect can be in every football supporter in the world, thinking they could do a better job on the field when a player misses a goal. But it also extends to scientific knowledge. This also comes with a blur between facts and opinion on a subject, as if the individual is expert enough to develop a valid opinion on the matter.

When you want to verify your opinion, you may introduce a confirmation bias in your research : you may focus only on the sources validating your thoughts and not those which contradict it. It’s a classic beginner’s mistake in science experimentation.

It gets worse when you mix this with social media : the strength of internet is to be a amazing field for expression, with an emphasis on personal expression. Everyone can be a media. Every person on the planet can be plugged, subscribed, linked to your daily thoughts and opinions. Your followers counter becomes a treacherous measure of the validity of your sayings : you can be saying non-sense, if it has 3000 likes, that’s like 3000 people supporting you.

The paradigm of social media is to personalize your experience at an extreme level. On the basis of your navigation history, previous purchases, … very sophisticated classifiers can label you precisely : gender, age, sexual orientation, political orientation, interests. The website wants you to spend time on it, thus wants to give you only the content the more adapted to your “internet personality”. It basically encapsulate your experience with people exactly like you, with the same opinions and thoughts. It makes you happy but it doesn’t challenge your mind one bit. Add the fact that you also may be exposed to viral fake news, if you don’t have any “acquaintance” in your network, that actually correct this fact, you may believe it your whole life.

Let’s take the example of flat-earthers.

Flat-earth is a (surprisingly large) group of people believing that the Earth is flat and that all governments are lying about it. This is such an absurd idea that people didn’t really take them seriously and instead of carefully explaining why you don’t see the curvature of the globe on the horizon, people made fun of them. So they started to regroup, to post on YouTube and social medias nearly scientific content made by them that fools anyone naive enough or ready to “believe” : they started a community. This community feeds on mockery to amplify the faith of their members into this belief and to amplify the links between the members. It is a social organisation at its core.

Such absurd conspiracy theories don’t come alone : one conspiracy lead naturally to another, a phenomenon that separates even more these people from the rest of the society, making a change of mind nearly impossible.

Video from Mark Sargent about the Flat Earth '''Clues''' ... 1M views.

Flat Earth is born on the Internet from the incredible “knowledge” tools everyone have at their disposal : a search engine, blogs, forums, social networks. They were used in a biased way but this bias lead was reported on their whole internet environment, making it less easy to stumble on the ground truth.

I recommend watching the amazing documentary Behind the Curve on Netflix to learn more about this subject.

Trailer for Behind the Curve

Some random thoughts on "what-to-do-now"

The first essential idea is to reconnect with people : science is not accessible enough, especially when you’re wrong like Flat Earth. It is a very difficult issue to tackle and I don’t really have a magic answer. According to me, the education system in science introduce a lot of shame (especially in France) when you give a wrong answer, and a less fearful system may be beneficial to attract more students to science, to better integrate science in culture, etc.

On accessibility, academic science is like a menacing castle with huge walls : impossible to get in and people in it look down on you. We need to take down those walls and make science communication friendlier, more attractive. From my personal experience as a science communicator, linking science to a another topic, in appearance completely out of it, is a working solution. By colliding science and cinema together, I can attract cinema lovers to scientific topics easily. As previously said, being a science communicator is less about teaching than arousing the curiosity for science in general.

My video on the analysis of fluids dynamics in the VFX industry

Another idea I applied is to change the look of science. If you try to read a scientific paper, you may be giving up without really going into it. Scientific are not designers at all, and render an idea visually demands time they often don’t have, so most of the papers or posters are really austere and poorly attractive, without even mentioning the actual look of an equation, closer to hieroglyphs than words. Science communication must decipher science for the public and propose a more attractive look. On my channel, I use the visual esthetics of cinema to get unusual scientific content : by embedding scientific visuals inside a movie, I can make them fun to look at in a very easy and convenient way.

Of course, let's not forget the basic rules of science communication : always check and show your sources, don't be afraid to make mistakes and have the energy to correct them, submit your work to a variety of people to gain feedback, ... I will stop this here before it turns into a Linkedin motivational post.

Conclusion

I tried to give an view of science communication today, what is at stake, why it is so difficult and necessary in our world context and how to maybe make it better. I remind that this survey is, often like a science communication content itself, a restricted point of view on the truth.

Thanks for reading !

Update 2021: Jesus Christ, I read that differently after the Covid pandemic 😐