The endgame of Hades loves the binomial coefficient, while human brains hate it

Combinatorics is not dead. Let's take another stab at it.

Combinatorics is an area of mathematics primarily concerned with counting, both as a means and an end in obtaining results, and certain properties of finite structures. It is closely related to many other areas of mathematics and has many applications ranging from logic to statistical physics, from evolutionary biology to computer science, ... and game design!

Hades blossoms in the repetition of runs, so of course I would do more than one article on it. I recommend reading the first article before this one though!

The size of the Pact of Punishment

The infernal Pact of punishment.

The Pact of Punishment is the main feature driving the endgame of Hades, unlocked after your 10th successful run.

At this point of the game, you are in a good spot : you invested the different currencies of the game into improving the power of Zagreus, you spent approximately 20 hours in the game already so you know the game systems, enemies, weapons and characters well.

You progressed too much! The game is too easy for you! Let's make the game progress then. But on the contrary to most "high difficulty" modes you can encounter, Hades lets you choose the stick to be beaten with.

Indeed, the Pact of Punishment lets you customize the increased difficulty of your run through control of many parameters of the game : health/speed/power of your enemies, alternate versions of the bosses, time limits, ... The smart thing here is to tye progression with the procedural generation of the dungeon in order to keep discovering things, weapons, rooms, etc late in the game.

All of those changes adds up in a single value exposed to players: heat. And so naturally, the game encourages you to complete the game with increasing levels of heat, for every weapon form there is, each new heat level giving access to precious resources that you can only loot once per level of heat and per weapon.

Giving the players the choice of their challenge is a genius move, as it involves them much more in the conception of the rules of the game, something utterly motivating. I believe you'll see this approach being used more and more by the industry.

Shadow the Tomb Raider drops the overall difficulty [Easy, Normal, Hard] for something more granular on its 3 gameplay pillars: combat, exploration, puzzle.

But exactly how many choices does this kind of menu create for players? How many configurations of the Pact of Punishment exist?

Well for the total number of configurations, the answer is really easy to compute. As reminder here is a summary of the Pact of Punishment options, and how many "ranks" there is per option:

| Condition | Ranks | Condition | Ranks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hard Labor | 5 | Underworld Customs | 1 |

| Lasting Consequences | 4 | Forced Overtime | 2 |

| Convenience Fee | 2 | Heightened Security | 1 |

| Jury Summons | 3 | Routine Inspection | 4 |

| Extreme Measures | 4 | Damage Control | 2 |

| Calisthenics Program | 2 | Approval Process | 2 |

| Benefits Package | 2 | Tight Deadline | 3 |

| Middle Management | 1 | ||

| Total | 37 |

Like before, let's think about what happens when a player makes a configuration:

- On the first option "Hard Labor", I have 5+1=6 choices, the 5 ranks and the choice to not activate this option at all.

- On the second option "Lasting Consequences", I have 4+1=5 choices, the 4 ranks and the choice to not activate this option at all.

- You get the idea: on option n°X, I have n+1 choices, n being the number of ranks possible in this option.

The final number of configurations is the product of the possible choices at each step. Thus:

Close to 70 millions possibilities! Not bad for just 15 options!

You can set up your own options and calculate the total number of configurations directly below:

So calculating the total is pretty easy right? What if I want something a bit more subtle now?

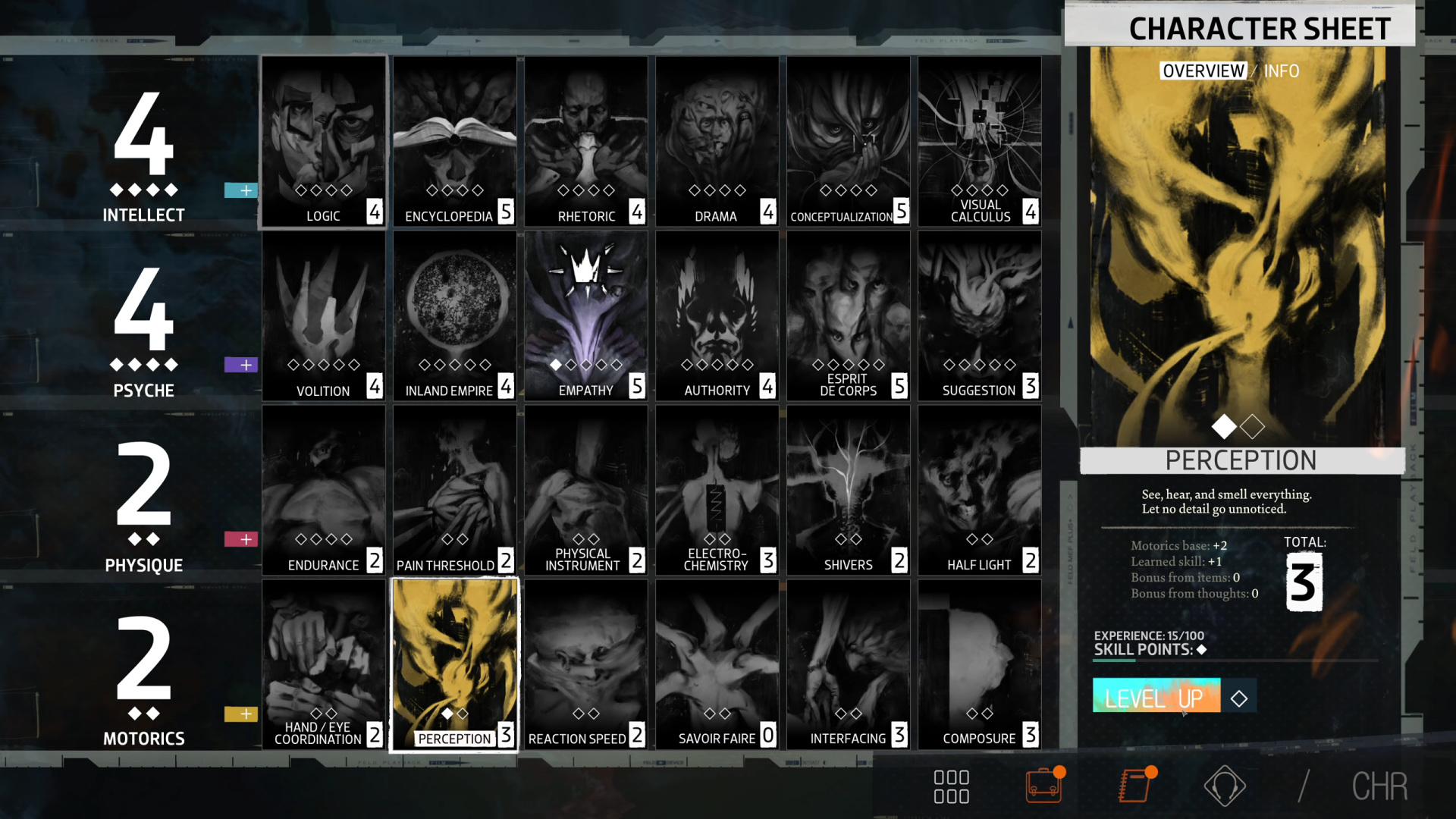

Because of the heat value exposition, the Pact of Punishment looks a lot like a point attribution system. Something that you would see in for a character build in an RPG for example.

Disco Elysium makes you spend skill points in variety of sub-categories.

In Dark Souls, you spend souls to level up, and you redistribute your level points in the properties of your character: Vitality, Attunement, Endurance, ...

So, according to me, an interesting question would be:

At a given heat, how many configurations

of the Pact of Punishment exist?

Because each option has a different maximum attributed, it would make the whole calculation very very complex, so we'll make this much more simpler.

Let's say I have 10 points to distribute into 5 differents categories like this:

How many point distributions exist?

To discover this formula, we're gonna change the problem again and make it look like another problem where we might know the answer.

Fundamentally speaking, a distribution is an addition of 5 elements that equals to 10. So the question becomes:

How many ways to cut 10 in 5 exist?

Now let's say I represent 10 with 10 symbols such as this star . A distribution becomes something like this:

And other solutions might look this:

And for that matter, we can replace the symbol with a letter and the sign with another letter and the solutions will stay the same:

So the problem becomes:

How many words can we make with 10 A and 4 B?

Or in a more mathematic way:

How many permutations of 14 symbols (10 * and 4 +) exist?

In mathematics, we're saying that we're looking for the number of permutations with repetitions.

To discover this formula we first have to look at a simpler case where all the elements are distincts.

If all the elements are distincts (so permutations without repetitions), let's analyze what happens when we generate an arrangement:

- On the first pick, I have exactly n choices.

- On the second pick, I have exactly n-1 choices, because I can't choose

- On the third pick, I will have n-2 choices, because I can't pick the first two elements.

- You get the idea: on the pick n°X, I will have n-(X-1) = n-X+1 choices.

- On the last pick, I will have 1 choice.

The final number of arrangements is the product of the possible choices at each step. Thus: .

And this formula is quite literaly:

But now, let's reintroduce the fact that the elements are such that there are identical objects and other identical objects and (in our example and ).

For each of the permutations, we can permute the identical objects and the arrangement would be the same. And since we have elements, there are ways to permute those elements without changing the arrangement. Same thing for the other elements.

So the number of permutations of elements with identical objects and other identical objects is:

Thus, if I have points and categories, the number of possible distributions is:

As a consequence, the number of distributions of 10 points in 5 categories is:

Again, passing a thousand possibilities with those small numbers seems crazy, and I'll address this point in the next part. In the meantime, you can set up your own numbers and calculate the number of permutations directly below:

n =

15

k =

10

An interesting thing to note here is that:

The binomial coefficient finds its way into our calculus (as it usually does).

Also: we suck at math

You may have been surprised by the gigantic numbers the different calculus outputted. The thing is: we are really bad with dealing with huge numbers. It's really difficult to get a natural hunch about combinatorics, because our brain is not natively wired for it.

An indian legend tells the story of the king Belbik who promised a reward for anyone who could distract him out of his boredom. The brahmin Sissa invents chess to the delight of the king, who asks Sissa how he wants be rewarded. Sissa tells the king to put one grain of rice on the first square of the chessboard, two on the second square, four on the third, and so on doubling the number of grains on each square : Sissa will only take the grains on the 64th square of the chessboard. The king is amused by this request and accept immediately. Here is what the numbers would look like on the chessboard:

You can imagine the drop of sweat on the face of the King Belbik now. (Source wikipedia)

The 64th square would contain grains of rice, 10 billions of billions of grains, so 300 years at the actual rice mondial production rate! This quantity can't be hold on a single square since if we put the grains on the area of Paris, the layer would be 2km tall, weighing 200 billions of tons (source).

The king didn't anticipate the crazy growth of a number doubled 63 times, probably because 63 is already a big number to apprehend for us! Like the king, nowadays against the exponential growth of the pandemic or climate change, we are not equipped mentally to imagine the consequences.

Sissa only asks for the quantity on the last square, since the last square contains as many grains as the rest of the squares on the board. Another fun and unintuitive property of this problem.

We all have a lot of automatisms in order to simplify an issue, trying to bring it under 10 in order to solve this on our fingers. Thus, if I come across a menu with 10 points to distribute across 5 sliders, I will see 5 choices to make, not 1 choice out of 1001 combinations. To further cancel this potential complexity, most games won't allow you to reinvest freely your points into an entirely new build: you spend your points one by one, without reimbursement, so you make your way into the system, 5 choices at a time.

As designers, programmers, game makers, ... we might know the full complexity of our systems, but we must never assume that players will or should have that knowledge.

Conclusion (bis)

Like any scientific measure, sizing your game systems must be analyzed and put in context. A big number doesn't necessarily mean big in-game value. And that's what I find fascinating about game design: its defiance towards mathematical logic.